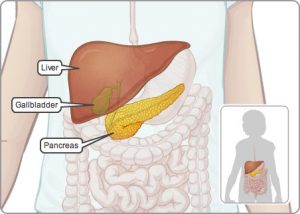

Gall bladder

The gall bladder is a pear-shaped organ, between seven and fifteen centimetres long, that sits just under the liver and shares the common bile duct with the liver. The gall bladder stores the bile, a yellow-green fluid containing water, cholesterol, phospholipids and bile acids to aid digestion, as well as waste products for excretion via the bowel, such as bilirubin. Bile, which is produced by your liver, acts as a detergent, breaking up the fat from food in your gut into very small droplets, so that it can be absorbed. It also makes it possible for your body to take up the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K from the food passing through your gut. The gallbladder is empty and flat after a meal, like a flat balloon: but before a meal it might be the size of a small pear and full of bile. In response to signals, the gallbladder squeezes stored bile into the duodenum (small intestine) through a series of ducts. In the duodenum, the bile breaks down fat.

What are gallstones?

Gallstones, lumps of solid material are formed in the gallbladder when the different elements, which make up your bile, become imbalanced. They usually look like gravel, but can be as small as sand or as large as pebbles, sometimes filling the gallbladder. They may take years to grow and there may be one or several.

Gallstones are formed from the chemicals in bile and may be:

- pure cholesterol stones – these are the most common type of stone and are made up of cholesterol, a type of fat. They form when cholesterol levels in your bile are much greater than your bile acid levels, causing the cholesterol in your bile to solidify.

- pure pigment stones – these consist of calcium and bilirubin (a pigment from broken down red blood cells) which have solidified. Pigment stones may form when the amount of bilirubin in bile is excessive.

- mixed stones – these are a combination of cholesterol and pigment stones.

Gallstones are more common in women than in men because cholesterol is a component of oestrogen, and the fluctuating levels of oestrogen need to be broken down to cholesterol and excreted in bile.

Gallstones can also form when the flow of bile is reduced. This may occur due to:

- damage to the liver (cirrhosis) or damage to the biliary tract which affects the secretion and flow of bile;

- long periods of fasting during which there is less requirement for bile, leading to a decreased flow of bile.

What are the symptoms of gallstones?

Many people live with gallstones without symptoms and are unaware they have them until the stones show up in tests performed for another reason.

The most common symptom of gallstones is pain in the abdomen, known as biliary colic. This is a pain that usually lasts between one and five hours (but sometimes up to eight) and varies from mild indigestion or discomfort, to severe pain. Sometimes the pain may be mistaken for a heart attack or a peptic ulcer; due to strong contractions as the gallbladder tries to expel a stone. The pain usually begins after eating fatty foods, though it can also wake you up during the night. These attacks are usually infrequent. Other symptoms may include nausea, vomiting or excessive sweating.

Symptoms indicating complications include:

- a high temperature of 38°C or above,

- persistent pain,

- a rapid increase in the rate of your heartbeat,

- jaundice – a condition in which the whites of the eyes go yellow and, in more severe cases, the skin also turns yellow (for more information see useful words),

- itchy skin,

- diarrhoea,

- shivering attacks – a sudden chill with severe shivering and a high temperature, similar to ‘flu’, is a sign that infection is building up,

- mental confusion,

- a loss in appetite.

Treatment

If gallstones have been discovered incidentally and are not troublesome, they are usually monitored and left alone. Some people may have one mild attack of biliary colic and no further trouble, while others have continuing problems. Painkillers, may be prescribed to control the symptoms of an attack.

The gallbladder is usually removed by keyhole surgery in a process called laparoscopic cholecystectomy which is performed under a general anaesthetic, using a fibre-optic tube with a tiny camera and a light on the end, called a laparoscope. A small incision is made and the abdomen inflated with carbon dioxide gas. Inflating your abdomen gives the surgeon a better view of your organs and more room in which to work. Instruments are then inserted into the abdominal cavity through three small incisions and controlled very precisely by the doctor, who is able to view your organs via a TV screen. The gallbladder is removed through a small cut in your navel. Afterwards the patient will have four small scars.

Mrs Physics’ Run in with a Gallstone!

Mrs Physics had this very problem and underwent the procedure mentioned. There was so much Physics to learn about during the whole process, e.g. the ultrasound scan, X-rays, CT scan, MRI scan, fibre optic laproscope, thermometers, stethoscopes, EGC devices and that is just the equipment.

However, before the gall bladder was removed a gallstone had to be extracted from the bile duct. Researching this, the duct was approximately 4 or 5 mm diameter (from which you astute ones can work out her age). However, the wonderful Mr Apollos, said that the stone in Mrs Physics’ duct was 28mm diameter, just over the size of a sixer marble. You can imagine how difficult that was to extract and all Mrs Physics can remember was waking up during the middle of this extraction to be told by all those around to keep still. A few complications arose, not least a puncture wound to the pancreas, which led to a two week stay in Ward 6; during which time Mrs Physics developed an admiration for the nursing staff, who not only were mentally but physically exhausted after their shift, an immense gratitude to Mr Apollos and Dr Greg and lots of new friends. She also felt that she was quite knowledgeable about all things gall bladdery; as it appeared most people on Ward 6 had the very same problem.

I dedicate this post to all those people who nursed me and the amazing friends I made whilst on the ward, but especially Karen and Jean.

This is the only picture of Mrs Physics that she has been pleased to show to others. It is pure brilliance, snapped my the surgeon on his camera. The second shot shows what will not be missed. Can you count the large numbers of stones and notice the different sizes. To quote Shrek

“Better out than in!”

Teachers: If you are looking for copyfree pictures of the gall bladder- feel free to use as desired.

![]()

If Mr B would like to share his gut, there would be lots of teachers and students that could learn so much and would put my tiny gall bladder in perspective.